Our Story

The story of how a method evolved for rewiring the emotional brain, the motherboard of humanity, using simple techniques, is like most. It all came down to a small group of dedicated people, with many foibles and missteps as well as a few moments of insight and clarity.

It all began in 1978 when, as a faculty member at UCSF taking part in a national adolescent health training program directed by Charles Irwin, Jr., MD, Laurel Mellin was researching how to help children stop overeating.

At the time, the brain was still a mysterious "black box," and stress was seen as a risk factor for certain diseases. Little was known about the underlying emotional brain, the storehouse of wires that either activated a stress and inflammation cascade that caused or exacerbated most health problems or a healing chemical cascade that promoted healing and well-being. The idea that people could control their own emotional brain, with its capacity for exceptional resilience, as well as rewire various unwanted blind spots and errant drives through using simple tools, was unfathomable.

Mellin sensed that something was missing in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), that it was not addressing the root cause of the problem of childhood obesity, with its spotty results and high dropout rates. She began plumbing the depths of the university library (then based on paper journals and microfiche) until one day she found a 1940 study by Hilde Bruch, MD on the family frame of children. The parenting style missed the mark of secure attachment, and she interpreted that the problem was a missing emotional connection between parent and child that set off “something” that made the children overeat. She taught the families in her clinic how to emotionally connect, using simple tools like asking "How do I feel?" and "What do I need?” This led to the development of the Shapedown Program, which was widely distributed in the U.S. in the 1980s and 1990s.

Unknowingly, in making emotional skills core to her intervention, Mellin moved past the accepted treatment of using conscious thoughts to control behaviors. Instead, users bypassed thoughts to connect with their emotions. They stepped through the portal of the emotional brain and into the underworld of the unconscious mind and unlocked possibilities of doing the unimaginable: self-control of physiology and the errant pathways in the brain that caused emotional and behavioral problems. Emotions were no longer psychological, but experiences that if adroitly managed could change the chemicals and electricity in every cell of the body.

Exploring how to work with multi-layered emotions would consume her for the next 40 years. She built on Sigmund Freud's most fundamental premise that faulty wires in the emotional brain were the root cause of emotional and behavioral problems, and later research from New York University and UCSF researchers showed that the human brain could change, physiology had two distinct categories, and fear memories could be erased

Transitioning to treating adults

The children's program was widely distributed in the U.S. and Canada, and Mellin began adapting the tools for the adult brain, launching The Solution Method in the early 1990s.

Mellin recalls, "During puberty, the brain switches from processing life by sensing and feeling to using the more developed thinking brain to figure things out. This creates a 'thinking brain barrier' so it takes some retraining to put feelings first and process them effectively. Only by feeling our feelings do the circuits in the emotional brain change, so this is an important adjustment. Also, suppressed emotions turn balanced emotions that are easy to process into toxic emotions that become persistent."

Mellin looked for a way that adults could untangle stress-induced toxic emotions. She began experimenting with a technique from psychologist John Gray. He espoused expressing anger, then sadness, fear, and guilt, to find acceptance. Still today, acceptance therapies are popular, however, Mellin's work suggested that the brain's natural processing of negative emotions, when sustained and not interrupted by thoughts, led to something even better than acceptance: joyous feelings.

She recalls, "I was counseling an obese boy in the emotional tools. He was furious that his father had brought him to see me. His anger came tumbling out, followed by sadness, fear, and guilt, but then, to my surprise, his emotions turned positive. His face lit up and he said he was happy, proud, hopeful, and grateful. Under his stress was joy."

Mellin's simple formula for emotional fluidity and turning stressed-out emotions into positive feelings became central to the method but more important, it suggested an underlying simplicity to emotional health. No matter what the untoward emotion (hostility, depression, anxiety, shame, numbness, or false highs), applying the emotional resiliency process led to joy. The diversity of emotional pathologies transformed into a singular state of emotional positivity.

Advances in science lead the way

As Mellin continued to develop the method not just for obesity but for a broad range of stress-related problems, a groundswell of science was changing health care. Three advances, in particular, would radically impact how she thought about the tools: neuroplasticity, stress physiology, and allostatic load.

The first of the three discoveries was made by Michael Merzenich, PhD, also on the faculty at UCSF, who showed that neuroplasticity continues to occur after childhood. The adult brain can change. His work in cognitive neuroplasticity to this day is the most respected in the field of neuroplasticity. Merzenich and Mellin met over the years, in kitchen table conferences and at his Posit Science headquarters, to explore the power of positive emotional plasticity and the power to use neuroplasticity to change the emotional brain to promote resilience. This brain-based health model remains core to EBT today.

Meanwhile, advances in research were radically changing how we thought about stress. Far from being just a risk factor for disease, chronic stress was increasingly being seen as a root cause of most health problems and interfering with health-promoting behaviors like sleep, nutrition, and exercise. Two major discoveries made stress more important, but also, farther beyond the power of traditional health care to remedy.

The second of the three breakthroughs was made by neuroscientist Peter Sterling, PhD of the University of Pennsylvania. He discovered that when stress overloaded the system, the brain defaulted to a process called "allostasis." Unlike its tamer counterpart, "homeostasis," which is self-correcting and gracious, allostasis has no shut-off valves and causes all domains of life to careen out of control. Compare eating an extra bite of food to binge eating a bag of cookies or experiencing a flash of anger versus going into a violent rage.

Although Sterling and his colleague Joseph Eyer discovered allostasis, there were no clinical methods then to quickly shut off stress overload response in real-time. Medications that quiet this “garage band” of dysregulation did not result in a symphony of physiology, as they were addictive. Allostasis was the problem, but it appeared to be untreatable. Emotional connection to others and exercise could be helpful, but in stress overload, strong drives toward isolation from others and lethargy made those strategies challenging to initiate.

The third discovery was made by Rockefeller University's Bruce McEwen, PhD, who coined the term "allostatic load," which was "the end of stress as we know it." According to McEwen, repeated episodes of allostasis lead to wear and tear and deleterious adaptation in the brain and body. From McEwen, we learned that it was not momentary stress, but these cumulative changes or one's “allostatic load” that is the best predictor of mortality. If allostasis was difficult to combat, treating a persistent state of allostasis was even more daunting. A formidable literature on allostatic load followed. The missing link was a brain-based way to address the root cause of allostatic load: the strength and dominance of an individual's reactive, allostatic wires.

Mellin met McEwen when he was a visiting professor at UCSF and they discussed EBT and the prospects of the method for reversing allostatic load. Later when Mellin was collaborating with Mary Charlson, MD at Weill Cornell School of Medicine on EBT research, Mellin and McEwen met in New York to continue their discussion.

According to Mellin, "When I spoke with Bruce about the power of emotional plasticity to change allostasis, he was excited. His warmth and graciousness, as much as his devotion to the science of allostatic load, helped me hold onto a vision of the more profound possibilities of EBT. Bruce passed away in 2020, but his influence on EBT and his many other contributions to neuroscience continue."

The method embraces neuroscience

Piecing together how to use brain plasticity and emotions to improve health and change behavior slowly evolved until 1999. Then, a team of psychiatrists at Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute headed by Fari Amini, MD wrote a book on how to rewire the limbic brain, the less primitive part of the emotional brain. A General Theory of Love mapped out how emotional circuits change by repeated experience. When she read this, Mellin had a sense of recognition. The repeated use of her emotional tools over time seemed to produce lasting changes. Could it be that emotional neuroplasticity was the mechanism of change?

She sent off a copy of her first book, The Solution, and her research to the authors, who all lived nearby, to ask them about that possibility. Weeks passed without a response, then late one day when she was at home, the phone rang.

Mellin recalls, "I answered the phone and heard the deep, soft voice of Fari Amini. He said he had received my materials. He paused for what seemed like an eternity, and then, with an almost accusatory tone, he inquired, 'Where do you live?' I told him. He responded, 'You have discovered a public health way of rewiring the limbic brain. You could live anywhere in the world, but you live only one mile from me!'"

Their subsequent meetings helped Mellin see the method as a potential way to rewire the emotional brain. Her next book on the method, The Pathway, became a New York Times bestseller. This book helped introduce the method to the public, and it also brought it to the attention of Igor Mitrovic, MD, a neuroscientist and professor of physiology at UCSF, who helped move the method to the next level of scientific rigor.

A chance recommendation

As the story goes, Marta Margetta, MD, a stress researcher at UCSF, spotted a publisher's advertisement for Mellin's book in a health journal. Her partner, Igor Mitrovic, (see his last lecture at UCSF about the method) had been quite stressed. Margetta encouraged him to read The Pathway, as it was written by another faculty member at the university.

Mitrovic tried an emotional technique from the book. In just a few minutes, he felt a glow all over and thought, “How did this woman figure this out?” Right away, he contacted Mellin, joined a group program to learn the method, and within months was collaborating with Mellin.

What had eluded Mellin was how to sew together emotions, stress, and behavior change, but this was the core of Mitrovic's expertise. Week after week, as they taught courses on EBT to medical students, Igor opened Mellin's eyes to new bodies of scientific endeavor, including those by neuroscientist Antonio Damasio, PhD. According to Damasio, emotions were not psychological, but instead they had biological underpinnings as part of a physiological loop that delivers essential information to the brain and body for surviving and thriving. Damasio contended that in using emotions to describe physiology, it is the feeling of joy that indicates the optimal workings of the body and brain. Hence, joy became the goal of using the EBT tools.

The biological utility of emotions took another step forward when Harvard University's George Vaillant, MD proposed that joyous emotions are evolutionarily based to guide us to become more spiritual and kinder people, and to enable us to recover from trauma and continue to evolve.

As people began using the method over time, Mellin could see that their needs in training changed. At first, they needed to use the tools to address problems, such as anxiety, depression, work stress, unhealthy habits, and relationship issues, but they stayed with the method to experience more of the higher rewards of life. Their increasingly-connected brain (“neural integration”) unleashed a natural desire to seek higher purpose and, at the same time, rewire the past and live more fully in the present. EBT leader and psychotherapist Judy Zehr, LPC, MHRM, a specialist in attachment science, suggested that the method promoted acquired secure attachment, often a central goal of psychotherapy. Dave Ingebritsen, PhD and the late C. Anne Brown, PhD shaped the use of the method for those most at risk of psychopathology. Mellin developed advanced courses in the method to enhance that emotional evolution, making the EBT program a neuroscience-based advancement of Erikson's developmental stages. These courses are now in their fourth edition.

Something was missing

Rates of stress-induced conditions began to rise in the 1990s. The speed of change, shrinking resources, and information overload were causing harmful stress to be ubiquitous, and no new methods for overcoming allostasis had emerged. Mellin noticed that the tools helped many people, but not those in extreme stress overload. She started to lose confidence in the tools. Then in late April 2007, Mellin's mother was admitted to intensive care for respiratory failure

Mellin recalls, “I was so depressed about my mother's declining health and one morning awoke about 4 a.m., feeling bone-chillingly alone - in extreme stress - and the tools didn't help me. Also, I remembered Igor speaking about EBT in a class on the method for medical students the previous evening on the biologic essentiality of positive emotions and eudonic rewards. In a moment of insight, I realized that the entire system I had spent 20 years developing fell short. It was based on three emotional states, but there were clearly two more to cover extremes, one to treat stress overload and the other to access states of rapture and joy. With five stress levels, asking 'How do I feel?'' was not enough. We needed to ask an entirely new question: 'What's my number?’”

After this realization, there was no turning back. Her mother passed away on May 1, and in the next three years, Mellin grieved, cared for her father, and developed a new approach to the method: The EBT 5-Point System of Emotional and Behavioral Regulation.

A new paradigm: rewire the stress response

Even in 2007, the method lacked a conceptual basis. The core research team, Mitrovic and Mellin, along with Lynda Frassetto, MD and Lindsey Fish, MD, found recognition of five brain states in the work of Bruce Perry, MD, PhD on five neurophysiological states. Despite this, the method was missing an overarching, scientific explanation for the clinical outcomes that were observed. Research findings on EBT showed lasting effectiveness after the end of treatment in adults and adolescents , suggesting that the method was addressing the root cause of the problem. The question remained: why?

Then one day in late 2010, Mitrovic, Frassetto, and Fish were huddled in his office, when Mitrovic suddenly exclaimed, "EBT is rewiring the stress response!"

Soon thereafter, the core group would propose EBT as a new paradigm in health care, rewiring the emotional circuits that control the stress response and resiliency. The method seemed to be standing up to its original name, The Solution, but they were advised that no researchers would study a method with such an unscientific name. Besides, the tools gave people a way to control their emotional brain, so they renamed it Emotional Brain Training (EBT) and developed Emotional Plasticity Theory to propose the method's conceptual basis: all creatures have survival drives that are encoded in emotional memory to promote adaptive self-regulation and survival and the self-directed targeting of these circuits for change is a plausible neuroscience-approach to health.

Yet Mitrovic's moment of realization was electric. Instantly, he began drawing out the mechanism on his whiteboard, a favorite learning incubator of medical students. EBT was changing the brain's stress wiring. There were two circuit types. First, he drew a pristine, balanced isosceles triangle, which he called a homeostatic circuit. It promotes resilience and health. Then he drew another a deranged tangle of triangular shapes, careening out of control. That was an allostatic circuit, which triggers reactivity, chronic stress, and disease.

An overarching framework

This vision was a brave act. Scientists tend to be reductionistic, finding esoteric pathways and small differences, yet Mitrovic proposed an overarching concept of neurophysiology. Neural stress circuits were either effective ("stress-resilient") or ineffective ("stress-reactive"). This was a huge breakthrough in health care.

First, the elusive, unconscious circuits that control our experience of life now had a name, so that instead of their being mysterious, things only psychologists and psychiatrists knew about, they could enter mainstream health care and self-care. There were only two types of circuits, which was simple enough, but with that basic differentiation made, EBT could evolve and create a language to describe circuits in actionable terms. People could differentiate their Core Circuits (unconscious beliefs) and their Survival Circuits (triggered drives and responses) and apply specific techniques to strengthen or weaken them.

Second, this took the psychological into the realm of biology. As all emotions, thoughts, and behaviors are activations of these wires, problems and issues were wiring activations. Switching them off and, over time rewiring them, was something anyone with sufficient skill in EBT could accomplish. Mental health had a new resource for helping people help themselves.

Third, an answer to Mellin's original concern, the limitations of the effectiveness of behavioral and cognitive behavioral therapy, became clear. With a model of EBT switching on and off neural stress circuits, the target became not the behavior, but the underlying wires. Neuronal stress circuits include three phases: 1) an initial subcortical emotional response, followed by 2) activation of unconscious expectations, and last, 3) a return from stress to a state of well-being. Behavior is the last of the three phases, in essence, the "tail end of the circuit." Seeking to change a behavior without switching off the emotionally-activated biochemical and electrical impulses that were driving it did not make sense.

Last, the calls of leaders such as Tom Insel, MD, the director of the National Institutes for Mental Health to turn away from the overuse of chemical treatments (medications) for mental health problems and toward identifying and changing circuits suggested a practical means of promoting wiring changes. Insel gave a formal "Grand Rounds" at UCSF in 2012, proposing a shift to rewiring faulty circuits.

It's all about the circuit

Insel's advocacy for targeting circuits came at a time when the diagnostic criteria in the mental health field were imploding. They were not based on physiology but on symptoms and were becoming complex and convoluted, a sign that they may not have been mirroring how the mind actually works. EBT offered a system that is based on how the brain works, on neurophysiology, and a fresh way to move past diagnoses much of the time. People discovered their allostatic load ("set point") and their wires and used the tools to switch out of them, or over time, attempt to rewire them.

The pre-neuroscience system of mental health was largely based on cognitive functioning, and as stress levels continued to rise, the effectiveness of that functioning in modern life came under question. New York University researchers showed that cognitive approaches are ineffective at switching off the high stress levels common in modern life as behavioral, cognitive, mindfulness, insight, and relaxation strategies all rely on effective cognitive control. With behaviors and thoughts not marshaling enough power to switch off the stress response, cracking the code on emotions was the only self-directed option that remained. The EBT Tools were designed to release stress rapidly with a burst of healthy anger, followed by emotions flowing from negative to positive. This enabled users to talk briefly about what was bothering them, for long enough to activate the reactive wire that fueled it, then to rapidly release stress so the thinking brain could stay online and orchestrate effective self-regulation. This new way of processing emotions is unique to EBT.

One process has two benefits

Also, NYU researchers found that fear memories that are stored in the unconscious mind, potentially reactivated for a lifetime, could be erased. Erasure or "reconsolidation" of circuits is the only intervention strategy that research has shown has a chance of producing long-term results. The key to erasure was that the wire had to be stress activated for a moment prior to delivering a new message or experience to the brain. Without stress activating, the response seemed to disappear but was rapidly reinstated. The excitement about reconsolidation is substantial as, without lasting results, dependency on the treatment - medications, psychotherapy - or surrender to discomfort is likely. Health care expenditures skyrocket.

The key to reconsolidation is the adaptive use of stress. To unlock and update a faulty wire takes accomplishing the level of stress that one was in when it was encoded but being able to stay present to one's emotions and change the faulty message. For example, when being triggered to overeat, it works to release the emotional stress rapidly and switch the circuit's message from "I get my love from food" to "I get my love from inside me." Without the skill to stress activate and target the wire, then stay aware of one's feelings, the wire with its unwanted drives continues to be stored in long-term memory and reactivated, perhaps for a lifetime. With an updated wire, the drive to overeat fades and weight loss and improvements in health are more likely to be lasting.

The research showing that stress can be used adaptively for rewiring gave a scientific rationale for the use of the EBT tools extending from stress reduction and resilience to targeting and rewiring the errant circuits that have traditionally been addressed in psychotherapy.

Mellin said, "This research supported the EBT practice of intentionally using the tools, essentially choosing to bring to mind something that is bothering you to clear away the reactive wire. We revised the program to be one of progressive rewiring of the brain, starting with learning the tools to alleviate stress, then learning the nuts and bolts of rewiring circuits, and last, going through advanced courses to rewire the brain for health, happiness, and emotional and spiritual evolution."

An online community for emotional connectivity

In the early 2010s, the method was flourishing, but its delivery systems were outdated. The training was transmitted through printed books and small pocket reminders of the lead-ins of the tools and was delivered only through onsite groups facilitated by health professionals. Joe Mellin, a business and technology designer, approached his mother saying that EBT should be global and that it would take a radical departure into using technology.

His vision was to build a technology-based platform, with users meeting in small, remote telegroups. Between sessions, they could use a mobile app for instant access to the tools, and for one-touch, private, confidential access to five-minute one-on-one peer support sessions by telephone to use the tools. Later, his concept of peer-to-peer support was validated by research. University of Kentucky researcher Kelly Webber, PhD showed in an EBT study"that these brief, between-session "peer connections" to use the tools in real-time predicted better health outcomes.

In 2013, health leader Walt Rose, now CEO of EBT, met Mellin and began collaborating with her to expand on the vision of making EBT scalable, neuroscience-based emotional and behavioral health care. His interest was in making a new resource available that shifted the health care system away from the overuse of medications and procedures and promoted people helping people help themselves to rewire the past and live a better present and future, using the peer-to-peer element of EBT. Rose and Mellin eventually married and are now life partners dedicated to moving the EBT method forward.

Personal power: rewiring for exceptional resilience

Perhaps the silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic is that stress is on everyone's mind. Two years before, 22 percent of the U.S. population was moderately-to-severely distressed , now 70 percent were in stress overload.

Just at a time when the health of our nation and our ability not only to bounce back but to find creative solutions to what ails us will predict our future, EBT has come into its own. More people want it, more people need it, and more people want to exert more control over the quality of their lives.

Mellin said, "If we have the EBT skills, stress can be good for us, as we can dip down into stressed states and spiral up with fresh ideas, new hopes and dreams, and more internal strength and fortitude to make our world and the world better places."

If we could do one thing, take one foundational step that would enable us not only to recover from the pandemic but to use our wisdom to move humankind forward, it would be to learn how to use the brain's natural and universal pathways of resilience.

The circle of support for EBT has brought together mission-congruent people, seeking to find a method that is at the nexus of neuroscience and spirituality. In 2021, these tools could make a huge difference in the course of history. However, that will take bringing this science and these tools to more individuals, families, communities, and organizations.

Mellin reflected on the method: "A participant told me last week that she loved EBT because it was reliable. I understand that, as I have taught the tools to the homeless, to people in intensive care units, and to titans from the entertainment industry and academia. I use the tools every day and I even taught them to my mother at age 86. No matter what the issue or problem, we can process daily life and soon find ourselves feeling vibrant, fully alive, and excited to move forward with purpose. That sounds like a solution to me."

Research

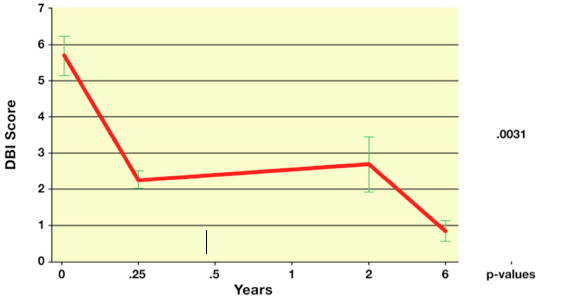

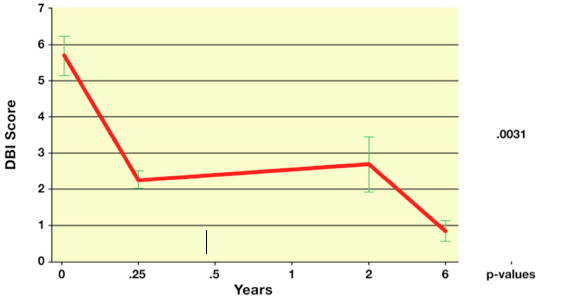

Lasting results

Improved Depression

Improved Weight

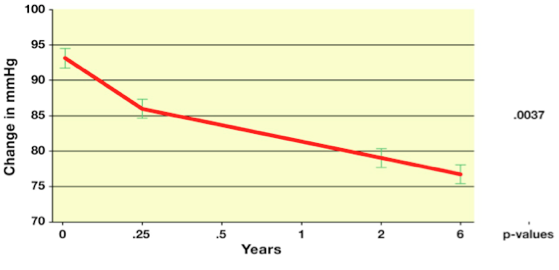

Improved Blood Pressure

An Evidence-based Program

- EBT produced resilience in less than 3 minutes

- EBT improved physiology-linked health indices

- EBT associated with lasting health benefits

- EBT sustained improvements in health at two years

- EBT trends in depression, blood pressure, addiction, and weight at six years

- Emotional intelligence, addictive behavior, and EBT

- Treats obesity, eating disorders and stress

- EBT technique is effective in promoting smoking cessation in veterans

- Improved depression, anxiety, stress, emotions, weight, and blood pressure in short-term EBT

- Sustained improvements at 15 months in depression, behavior, and weight in overweight adolescents

- Worksite EBT Improved Employee Emotional Health

- Physiological Brain States: New to EBT and Advanced

- Improved health and well-being in EBT Program graduates

Brain Based Health

- A new paradigm in healthcare

- Distress in 70% of the U.S. population

- The story of the golden age of the new healthcare

- The emotional brain encodes stress circuits

- Stress Circuits can be erased

- Rewiring Stress Circuits shows effectiveness

- Traditional methods do not erase Stress Circuits

- Rewiring is the only approach that shows lasting improvements

- The original conceptual paper on EBT